Regarding the Pain of Others, Decontextualization in the Media, and the American Penchant for Apathy

Thursday, October 1, 2015 at 11:53AM

Thursday, October 1, 2015 at 11:53AM The radio program To the Best of Our Knowledge recently aired several interviews as part of their Regarding the Pain of Others broadcast. The episode featured interviews the war photographer Susan Sontag (1933 – 2004), author of Regarding the Pain of Others, and Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar, creator of “The Rwanda Project” and who traveled to Rwanda during the immediate aftermath of the 1994 genocide there. Susan and Alfredo make numerous significant points, and transcribed below are some of the points that hit home for me. (Sidenote: if you’re interested in reading an excellent book on the Rwandan Genocide, as wells the roots of several other conflicts in Africa, I would highly recommend Bill Berkeley’s The Graves Are Not Yet Full.)

Interview with Alfredo Jaar:

Steve Paulson: What did you come away understanding?

Alfredo Jaar: I felt that human beings can do terrible things to each other. This is something I knew of course from history but I had never experience this in such a vivid and personal way. I went away feeling ashamed of being a human being. I went away want to commit suicide because I couldn’t believe that, as a human being living in the world today, I had allowed this to happen. I felt guilty.

Steve Paulson: Because there were news reports that this was going on while it was going on, and in fact there were plenty of reports that something terrible was going to happen even before it did.

Alfredo Jaar: Absolutely, but unfortunately it was on one hand played down; second, most media did not use the word genocide so we would not intervene because, as you know, there’s a convention that forces countries to intervene if it is officially a genocide, so the State Department asked not to use that word and most media complied. The way the media works today – everything is decontextualized. You open a paper, you might find a couple of photographs about this horror, but next week you have the new model from Toyota, and the next page you are invited to take vacations in Hawaii at a great price by this airline, and then you move on. So, everything is decontextualized, so an image of pain, of suffering, is drown in a sea of consumption in the media today. So it’s very difficult to affect change through the media in the way it’s built now.

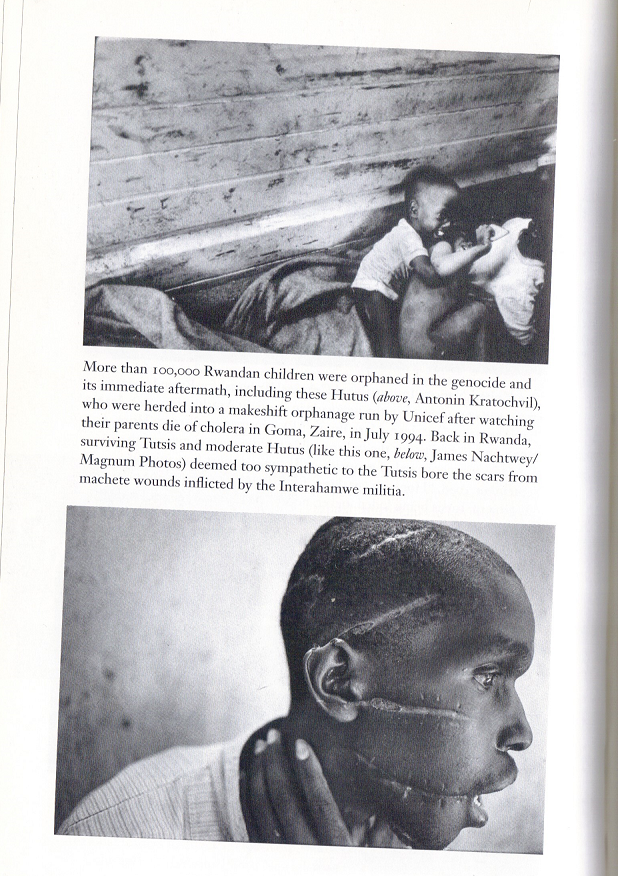

Image from: The Graves Are Not Yet Full

Interview with Susan Sontag:

Susan Sontag: There are two pivotal moments in the history of war photography. One is the Spanish Civil War, where for the first time a war was covered by photojournalists, most famously Robert Kappa, who had cameras that were portable. Before that photography was basically the camera on a tripod, so the photographer was not going into the thick of battle. But once the portable Leica and film that could shoot thirty-six images before reloading was developed, you had the photographer going into battle and producing images which really set the standard for what war photography could be. That was on the whole very partisan photography – the famous images from the Spanish Civil War are all from photojournalists who were on one side, namely the Republican side; they were against the fascist rebellion lead by Franco which did in fact triumph. And the Vietnam War, that was the second turning point where again, most all the photography was taken by partisan people who sympathized with the suffering of the Vietnamese and of the American soldiers – and they were not for the war. And a lesson was learned from the Vietnam War by governments making war: that was that one must not let photojournalists have free reign.

Steve Paulson: And you don’t see that anymore. I mean, in the first Persian Gulf War there are very few pictures of actual combat.

Susan Sontag: Actually, the model for that was in an even earlier war. A small war waged by Prime Minister Thatcher; and when the British expeditionary force was dispatched to Argentina to recapture some islands off of Argentina that the British owned, Thatcher essentially forbade journalistic coverage or controlled it so thoroughly that virtually no battle scenes or scenes of the carnage and the deaths were caused in that war [sic]…

Susan Sontag: It’s absolutely true that there is voyeuristic impulse in many people, in most people, and they will slow down to look at the car wreck and then say, “Wasn’t that terrible?” We are attracted in some way to these images; the basis on which we’re attracted is rather complicated. Maybe it’s that we want to experience that we are safe. You see, if I can go back to the idea of the whole book, Regarding the Pain of Others, what does the title mean? It means that we are safe, and we’re looking at something happening to other people, but we’re not there, we’re here. We’re here looking at a magazine or a newspaper, we’re in front our television sets, we’re looking at images on our computer, and the terrible things are happening somewhere else. So why do we do want to look at them? First of all we think that we ought to look at them maybe, we have an obligation to look at them, to know what the world is really like, maybe we have a particular identification with the struggle or particular interest in it, maybe we’re testing ourselves to see if we really can look at terrible things, like a kind of ordeal. But I think in all of these expereinces something is happening which I think is real and at the same time very questionable, that it’s there and its’ not here, and if you’re not looking at it, you’re not responsible.

Steve Paulson: In a sense it removes us from the suffering, and I don’t want to overplay this, but we can perhaps feel a little more virtuious by going through the pain of looking at these, but also in the back of our minds we know that’s not us, we’re safe, we’re innocent.

Susan Sontag: One, it’s not happening to us, and two, we’re not doing it. Now the second assertion may be a little questionable. If you’re country has gone to war with another country, do you have a responsibility to oppose that war? I think that the images tend to make us feel passive, but I don’t think, as I used to think, that they necessarily desensitize us. I think they only desensitize us when we’re told, “This is a, age old conflict, there’s absolutely nothing to be done about it, it’s hopeless,” then I think you say, “Oh that again,” and you switch the channel. But if you have been told that something can happen, something can be different; if you have another political context, I think these images can be very mobilizing and I don’t think you get used to them.

Steve Paulson: Well, also, I think we tend to feel these days that given the reach of the modern media, that we see everything, that we see all the horrors, but that’s actually not true, we don’t see the worst of it. Going back to the September Eleventh attacks. We saw repeatedly the planes smashing into the World Trade Center, we saw almost no images of the dead bodies, and clearly they were there, but people choose not to show those.

Susan Sontag: Yes there was a great deal of largely self-censorship, which of course is the most powerful form of censorship, of the images of World Trade Center and the Pentagon – there are virtually no images of the destruction of the Pentagon and of the people who were killed there – and there were a lot of photographs that were taken, this is well known, of very gruesome things at the World Trade Center. And what was the reason that the people who control the media gave about this? “This isn’t helpful,” or something you hear very often, “This isn’t good taste.” Now I’m very suspicious when people talk about good taste as a reason for not showing something. It’s felt to be unpatriotic, it’s felt to be demoralizing, there are all sorts of reasons…

Steve Paulson: Well, the other reason that’s often given is that it would be disrespectful to the families of the dead, that somehow it would be dishonoring the memory.

Susan Sontag: Yes, but that’s because Americans have the rather obscene habit of thinking that American lives are worth more than anybody else’s lives and American lives have an entirely different value than other people’s lives. We don’t have a problem about showing a foreign dead, we have a problem showing American dead.*

African-American Civil War Soldiers Burying the Battlefield Dead, Library of Congress.

*I disagree with her last point. If U.S news media regularly showed the foreign civilians massacred abroad by tax-payer-funded weapons; if the American public had to contend with an onslaught of images of manifold dismembered bodies of women and children destroyed by the bombs and bullets we’ve manufactured and launched, then many of our nation’s problems would be solved. The American people would demand an end to these wars, we’d bring the troops home, close foreign military bases, save hundreds of billions of dollars, and no longer would be washing our collective, figurative hands in blood. But instead of doing the smart and moral thing, we’re wading neck-deep in ignorance and consumerism, and shall one day drown in it all wondering what we did to deserve this.

Aaron |

Aaron |  Post a Comment |

Post a Comment |

Reader Comments